Like many other scientists of antiquity, few details of the life of Hipparchos are known with any certainty, though some aspects of it can be plausibly sketched in. According to ancient authors he was born in the city of Nicaea (Νίκαια) in the kingdom of Bithynia (Strabo 12.4.9, Aelian De Natura Animalium 7.8, Suda s.v.).1

Nicaea is now the town of Iznik in the Bursa province of northwest Turkey, which lies about 90 kilometres southeast of Istanbul. It was a Greek colony of no great antiquity which, by the time of Hipparchos' birth had already experienced a turbulent political history in the wake of Alexander the Great's death. Centuries later, it was to become famous as the location of the First Council of Nicaea (325 CE) which established the Nicene Creed and the rules concerning the date of Easter, and much later still the Second Council of Nicaea was held there (787 CE) which approved the veneration of holy images. Before then, it had been the birthplace of the Roman historian Cassius Dio (c 155 – c. 235 CE). However, in pre-Christian times, being the birthplace of Hipparchos was its only claim to fame.

The exact dates of his life are unknown, but from his documented career as an astronomer, which ranges through 35 years of observations from 162 BCE until 127 BCE, we can estimate that he lived from perhaps c. 190 BCE to c. 120 BCE using the conventional ancient reckoning of a 70 year lifespan or thereabout (which for various reasons seems plausible in his case).

Similarly, very little is known of his family but we may assume that it was ethnically Greek, at least on his father’s side, since his name, a fairly common one, is of typical Greek binomial form: Hipp‒archos, meaning ‘horse tamer’ or ‘master of horse’.2 In addition, we may suppose that it was at least moderately wealthy, thereby enabling him to get a good education and subsequently to pursue a life of study and travel, though it is likely that he also had some earned income through astrology, which in its horoscopic form was devised in Hellenistic times and had become increasingly popular.3 It appears from evidence of his observations in Ptolemy (Almagest 6.5, H1.478; 6.9, H1.525; 5.3, H1.363; 5.5, H1.369; 5.5, H1.374) that he spent most of his later life on the island of Rhodes and he probably died there (see below).

Again, next to nothing is known of Hipparchos’ education, but it is quite clear from his work that it must have been good. He was a careful reader, an astute textual critic and knowledgeable about the science and mathematics of his time. It is likely that as the son of a prosperous family he went to Athens or Alexandria to study (two great centres of learning of the period), or perhaps both. However, there is no direct evidence to support this.

|

| Temple of Apollo on the Acropolis of Rhodes. Image: Wikimedia Commons |

Reputation

An anecdote, recorded by the C2nd / C3rd CE writer Aelian (loc. cit.) attests to his skill in predicting the weather. The story goes that he once attended the theatre dressed in a leather coat because, despite the warmth and clear skies, he knew that a storm was coming. This anecdote cannot be true as it stands since Aelian places it in Syracuse which Hipparchos probably never visited and in the reign of Hieron II who died about thirty years before Hipparchos was born. However, the fact that the anecdote existed at all shows that Hipparchos was considered famous enough in later antiquity to have accrued at least one apocryphal story.4

|

| Photo by the author from the BM catalogue. |

As well as the Nicaean coinage from the later Roman period, it is clear from earlier sources that Hipparchos had become well known in intellectual circles in the couple of centuries after his death. Strabo, the Greek geographer (c. 64 BCE ‒ c. 24 CE), refers to him often in connection with the book Against Eratosthenes that Hipparchos wrote. The Roman lawyer and politician, Cicero (106 ‒ c. 43 BCE), mentions him in a letter to his brother (Ad Atticus 2.6.). Furthermore, the Roman writer Pliny the Elder (23 ‒ 79 CE) refers to him in glowing terms in his encyclopedia on more than one occasion (Natural History 2.12, 2.24). In the last case, however, it is unlikely that Pliny had actually read any of Hipparchos' works himself; his knowledge would have been second or third hand. Later, in the middle of the C2nd CE, Ptolemy refers to Hipparchos often, and much more than any other astronomer, in his major work the Almagest.

Travels

That Hipparchos spent his early life in Bythinia where he was born is not only clear from the evidence cited above but also from statements by Ptolemy ( Appearances ) that it was there that he made various astronomical observations for the sake of weather prognostication. There was a very common (and not wholly unreasonable) belief in ancient times, sometimes known as juridical astrology, that the risings and settings of stars correlated with certain weather phenomena like storms, not merely in terms of general seasonal effects, but in day to day specifics. Presumably, he was a young adult at this time, perhaps in his twenties, and may have been responsible for constructing or maintaining official parapegmata , which were a type of weather almanac.

However, there has been debate about whether Hipparchos spent time in Alexandria. Advocates for the idea have sometimes adduced as evidence the fact that he reports the occurrence of lunar eclipses there, which is based on a discussion in Ptolemy (Almagest 4.11, H1.344–8). However, as many have pointed out, Hipparchos could not have made these observations because they occurred before he was born: on 22nd September 201 BCE, on 19/20th March 200 BCE and on 11/12th September 200 BCE. Possibly the observations on which Hipparchos drew were made by Eratosthenes. In fact, it is clear from the context of Ptolemy's discussion that Hipparchos possessed many reports of eclipses before his own time going back to the C4th BCE including those of the Babylonians.

Another piece of evidence that has been adduced for an Alexandrian sojourn are the reports in Ptolemy ( Almagest 3.1, H1.194–6) of autumnal equinox observations which were listed by Hipparchos in his book On the displacement of the Solstitial and Equinoctial Points . There are six of them and the first four were probably made in Alexandria:

- 27th September 162 BCE at sunset

- 27th September 159 BCE at dawn

- 27th September 158 BCE at the sixth hour

- 26/27th September 147 BCE at midnight

- 27th September 146 BCE at dawn

- 26th September 143 BCE in the evening

Next, Ptolemy reports from the same book by Hipparchos a list of spring equinox observations carried out with similar accuracy (ὁμοίως ἀκριβῶς τετηρημένας):

- 24th March 146 BCE at dawn (but the observation made in Alexandria of the same equinox was at the fifth hour)

- 24th March 145 BCE

- 24th March 144 BCE

- 24th March 143 BCE

- 24th March 142 BCE

- 24th March 141 BCE

- 23/24th March 135 BCE after midnight

- 23/24th March 134 BCE

- 23/24th March 133 BCE

- 23/24th March 132 BCE

- 23/24th March 131 BCE

- 23/24th March 130 BCE

- 23/24th March 129 BCE

- 23th March 128 BCE about sunset

|

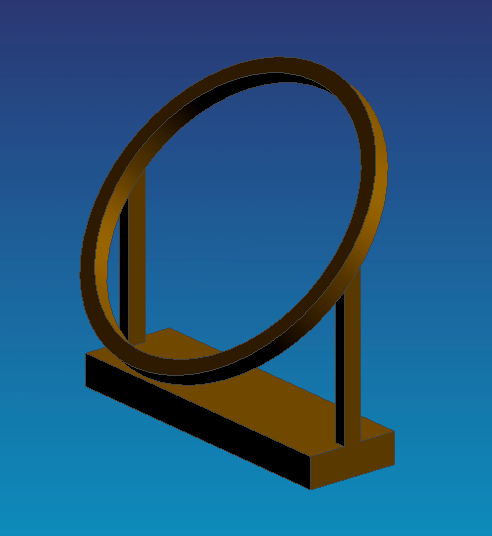

An equatorial ring which can be used to observe equinoxes.

When the Sun crosses the celestial equator, the shadow of

the upper part of the ring falls on the inside of the lower part.

Image licensed under CreativeCommons . |

And so from these observations it is clear that the differences in the lengths of the years have been altogether tiny. But, with regard to the solstices, I suspect that both Archimedes and I may have made errors in both observation and calculation of up to a quarter part of a day. However, the anomaly in the length of the year can be accurately perceived from the observations of the bronze ring situated in the so called 'Square Stoa' in Alexandria, which appears to indicate clearly the equinoctial day on which it begins to cast light onto its concavity from the other side.The reference to a solstices observations is interesting since we only know of one such that is preserved. It turned up recently in a new papyrus fragment (P. Fouad inv. 267A, PSI inv. 2006) in a work on solar longitude by an unknown author. In the fragment, the author refers to the summer solstice of 26th June 158 BCE as being observed by Hipparchos. Unfortunately, no time of day is given. Presumably, as the quotation suggests, Hipparchos made many such observations, but was probably dissatisfied with their accuracy, realising, as did Ptolemy, that they were intrinsically more difficult to carry out.

In the quotation above, the bronze ring referred to was an equatorial ring which was mounted so as to be parallel with the plane of the celestial equator. Normally the Sun would illuminate the lower part of the ring, either from above (in summer) or below (in winter); but on the day of the equinox the shadow of the upper part would cross the lower part. At the spring equinox in Alexandria the shadow would move across the lower part of the ring from top to bottom, and in the other direction at the autumn equinox. The time taken for the shadow to cross would depend on the dimensions of the ring, but the change in the Sun's declination at the equinox is about 24' in 24 hours which corresponds to a change in ecliptic longitude of 58' 17'' as Ptolemy notes (Almagest 3.1, H1.197). If the equinox happened during the night, the time could be estimated by interpolation from the observations on the days before and after.

Ptolemy goes on to note (Almagest 3.1, H1.197) that the two bronze rings that he knows of in the palaestra (wrestling area) in Alexandria were not very accurate, and that one of them sometimes showed the shadow crossing the lower part twice on the same day.7 The palaestra in question was probably part of the large Gymnasium complex described by the geographer Strabo (17.1.10), and the older ring may have been the same one referred to by Hipparchos (albeit after an interval of nearly 300 years) since the architectural form of a palaestra was usually that of a square stoa (four sided colonnade).8

However, it seems clear from Hipparchos' description that, although he did not use the equatorial ring in Alexandria for observation #7 (he was not there), he was familiar with it and trusted someone enough to include in his report their observation of the equinox using it. In fact, the spring equinox on 24th March 146 BCE occurred at 15:14, over 9 hours after dawn, so both of the observations reported by Hipparchos were wrong, but the one in Alexandria less so.

The key to this is understanding Hipparchos' attitudes to the observations of others. In order to undertake his various calculations, he needed a long record of observation and was thus obliged to use (as was Ptolemy) observations carried by people who lived before him. But we know both from his own words in his only extant book, the guide to the night sky known as the Commentary on the Phenomena of Aratos and Eudoxos (CPAE passim), and from Ptolemy (7.1, H2.3), that Hipparchos took rather a dim view in general of the accuracy of the observations made by others. It seems likely, therefore, that when he describes observations as being performed 'very accurately', he would not have said this unless he had either made them personally or they had been made by someone he knew well or perhaps had trained. Essentially, this is the same argument made by Fotheringham (1918, 408) which was so abruptly and loftily dismissed by Neugebauer (1975, 276 note 20).

A further complication is raised by Dicks (1960, 6–8) who points out that Alexandria was an unattractive place for scholars and scientists in the C2nd BCE owing to political turmoil and, indeed, outright repression. However, this is to take too broad a brush to Alexandrian history. He is right, of course, to point out that the golden age of Alexandria was in the C3rd BCE, when Ptolemies I to IV were on the throne (305 to 204 BCE), and when its great library and mouseion attracted scholars such as Euclid of Alexandria, Zenodotos of Ephesos, Kallimachos of Kyrene, Apollonios of Perga, Apollonios of Rhodes, Eratosthenes of Kyrene and Aristophanes of Byzantion. And he is also right to say that in the early C2nd BCE the political power of Alexandria began to decline, due to ongoing conflicts with the Selucid Empire and a good deal of domestic unrest from the native Egyptian population as they struggled to wrest more power from the Greek upper classes.

However, with the second reign of Ptolemy VI Philometer (163 – 145 BCE) who ruled jointly with his sister and wife, Kleopatra II, the political situation stabilised. And it was not until his death and the assumption of power by their brother, Ptolemy VIII Euergetes in August 145 BCE that things changed. Ptolemy VIII killed Ptolemy VII, the son of Ptolemy VI and Kleopatra II, and then married the latter (also his sister, of course). There followed a purge of the intellectuals who had supported and thrived under Ptolemy VI. Amongst those who had worked in Alexandria under the reign of Ptolemy VI were: Aristarchos of Samothrace, the greatest literary critic of the era; and his students, the chronographer Apollonios of Athens and the grammarian Dionysios Thrax; the historian Herakleides Lembos; and also the mathematician Hypsikles of Alexandria. These and many like them were either killed or driven into exile.

Thus, there is clear period of about eighteen years of relative peace and stability in Alexandria when we know that various scholars were working. And so, on closer examination the argument that the political atmosphere in Alexandria was somehow too hot for intellectuals in the mid C2nd BCE falls by the wayside. The attractions of Alexandria to a young astronmer were obvious. As well as being a centre for the relatively new science of horoscopic astrology (a blend of Babylonian and Egyptian practices), it had long tradition of astronomers working there such as Euclid, Timocharis, Aristyllos, Apollonios and Eratosthenes, all of whom left a record of observations or writings which were probably available for copying.

We know that Hipparchos ended up in Rhodes but it may be reasonably asked if he went anywhere else. A case can be made for a visit to Athens. In his book, the CPAE, the only place other than Rhodes for which Hipparchos gives a latitude is Athens (unfortunately he gives it as 37° instead of the correct 38°). Indeed, he mentions Athens on four separate occasions (CPAE 1.3.12, 1.4.8, 1.7.21, 1.11.8) as a location from which to survey the sky. Hipparchos must have had a reason for choosing Athens as well as Rhodes for this purpose. An obvious, but unprovable, solution to this question is that he already knew someone there for whom he was writing his guide to sky.

We don't have to look far for a candidate. The CPAE was dedicated to a certain Aischrion, about whom we know next to nothing apart from the fact that his brothers (with whom he ran a business) had recently died, that he was on friendly terms with Hipparchos, and that he was sufficiently interested in astronomy (but no expert) to have studied the Phenomena of Aratos. Such a relationship was most likely to have formed from actual face to face contact over at least a few months.

Putting this all together, therefore, we can sketch out a plausible, albeit largely unprovable, biography of Hipparchos:

-

c. 190 BCE: Born in Bythinia, he grows up there and becomes an astronomer, carrying out observations for the purpose of weather prediction and possibly parapegma construction.

- c. 163 BCE: With Ptolemy VI established on the throne, Hipparchos travels to Alexandria possibly to study the new science of horoscopic astrology with a view to establishing himself as a practitioner in the field and to procure copies of observations by Aleaxandrian astronomers. He broadens the scope of his astronomical observations and cultivates relationships with other astronomers, at least one of which has an observational technique he can trust;

- c. 147 BCE: With tension growing between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid Empires and the political situation in Alexandria deteriorating, Hipparchos travels to Athens to seek out new clients and contacts (possibly stopping off in Rhodes for a while), and where he also makes the acquaintance of Aischrion who is to become a good friend;

- c. 146 BCE: With the destruction of Carthage and the quelling of Macedonia, the previously benign Roman foreign policy towards Greece changes abruptly, triggered by a rebellion of the Achaean League. The Romans destroy Corinth and subdue the rest of mainland Greece, formally turning it into two provinces. Hipparchos leaves Athens for Rhodes (already a long established ally of Rome), attracted by its reputation as a centre for learning and its relatively stable political climate. He settles there, living out the rest of his life practising astrology, astronomy and writing books.

NOTES

1. (Strabo) ἄνδρες δ᾽ ἀξιόλογοι κατὰ παιδείαν γεγόνασιν ἐν τῇ Βιθυνίᾳ Ξενοκράτης τε ὁ φιλόσοφος καὶ Διονύσιος ὁ διαλεκτικὸς καὶ Ἵππαρχος καὶ Θεοδόσιος καὶ οἱ παῖδες αὐτοῦ μαθηματικοὶ Κλεοχάρης τε ῥήτωρ ὅ τε Μυρλεανὸς Ἀσκληπιάδης γραμματικὸς ἰατρός τε ὁ Προυσιεύς.

Men famous for the their learning have come from Bithynia: Xenokrates the philosopher, Dionysios the dialectician, Hipparchus, Theodosius and his sons the mathematicians, and also Kleochares the rhetorician of Myrleia, and Asklepiades the physician of Prusa.

(Aelian) καὶ Ἵππαρχος μὲν ἐπὶ Ἱέρωνος τοῦ τυράννου καθήμενος ἐν θεάτρῳ καὶ φορῶν διφθέραν, ὅτι τὸν μέλλοντα χειμῶνα ἐκ τῆς παρούσης αἰθρίας προηπίστατο ἐξέπληξε: καὶ ἐθαύμαζεν Ἱέρων αὐτόν, καὶ Νικαεῦσι τοῖς Βιθυνοῖς συνήδετο ὅτι Ἱππάρχου πολίτου ἔτυχον.

In the time of King Hieron, Hipparchos once wore a leather coat in the theatre because he foresaw that there was going to be a storm brewing out of the current fine weather. Hieron marvelled at him and congratulated the Nicaeans of Bythinia on their good fortune since Hipparchos was a fellow citizen.

(Suda) Ἵππαρχος, Νικαεύς, φιλόσοφος, γεγονὼς ἐπὶ τῶν ὑπάτων, ἔγραψε περὶ τῶν Ἀράτου Φαινομένων, περὶ τῆς τῶν ἀπλανῶν συντάξεως καὶ τοῦ καταστηριγμοῦ, περὶ τῆς κατὰ πλάτος μηνιαίας τῆς σελήνης κινήσεως, καὶ εἰς τὰς ἀρίστους.

From Nicaea, a philosopher, lived at the time of the consuls. He wrote 'On the Phenomena of Aratos', 'On the Arrangement of the Fixed Stars and the Catasterisms', 'On the Monthly Motion of the Moon in Latitude', and 'Against Eratosthenes'.

The reference from Strabo is interesting because unlike the other famous people from Bithynia that he names, he did not feel it necessary to say what Hipparchos was famous for.

2. Some 20 instances of the name (belonging to what were at least moderately famous men in their time) are known from many places in ancient Greece and occurring at different periods (RE : s.v.). The LGPN records a total of 151 instances. Thus, the name was certainly not unusual.

3. For Hellenistic astrology in general see Campion 2008: 173‒184. Surviving horoscopes date from the first century BCE (Neugebauer and van Hoesen 1959: 76‒78). Alexandria was a centre for many forms of learning including astrology and it is possible that Hipparchos went there specifically to study it.

4. It is quite possible that this anecdote was originally attached to Archimedes who lived in Syracuse and at the right time, but he had no shortage of stories that were told about him. Perhaps someone borrowed this one to attach to the somewhat less famous Hipparchos. On the other hand, we do know from Ptolemy (Appearances) that Hipparchos was involved in weather prediction in his early career. It is always possible that Hipparchos did visit Syracuse at some point in order to collect works by Archimedes, some of which we he seems to have possessed in later life.

5. British Museum: Catalogue of Greek Coins: Pontus, Paphlagonia, Bithynia and the Kingdom of Bosporus , 1889. Catalogue number 97.

6. Fraser's confusion of astronomical and calendrical dating does not help his case, of course.

7. This phenomenon is difficult to explain. If we assume that the ring was 80 cm in diameter and in cross section 1 cm square, then the angle subtended by the shadow moving from one side to the other is given by arctan( 1 / 80 ) = 0.72°. This cannot be due to refraction as sometimes suggested since, even at the horizon, atmospheric refraction is not normally much greater than 0.5°, and at an altitude of just 5° is little more than 10 minutes of arc. The most probable explanation is that the ring suffered from a slight deformity. For further information see Britton (1967: 29–42).

8. For further discussion on the Gymnasium, see Fraser (1972: I.28–9, II.98 notes 222 and 223).

No comments:

Post a Comment